I cannot teach you how to draw, but I can teach you how to look at things differently to engage the visual, spacial centers in your brain. To do this, we have to work our way through a couple exercises. One will create conflict between the verbal and the visual centers of your brain, and the other will help resolved this conflict.

The first one involves thinking of our profile (or side view) of a face in the Vase/Faces drawing.

The excerpt below is from the wonderful book, “Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain” by Betty Edwards.

This exercise is specifically designed to help you understand the shift from the dominant verbal center of your brain to the subdominant visual center.

What you’ll need:

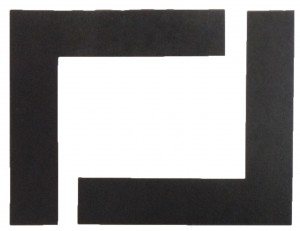

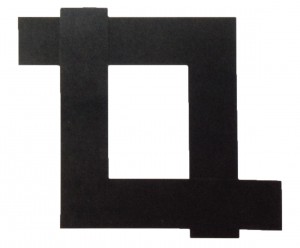

The picture above is a famous optical-illusion drawing called “Vase/Faces” because it can be seen as either two facing profiles or a symmetrical vase in the center.

What you’ll do:

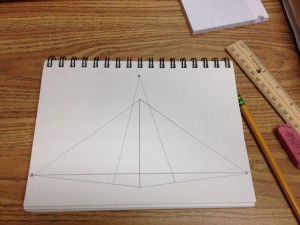

You will complete the second profile, which will inadvertently complete the symmetrical vase in the center.

Before you begin: Read all the directions for the exercise.

- Copy the pattern or print it out. If you are right-handed, copy the profile on the left side of the paper, facing toward the center. If you are left-handed, draw the profile on the right side, facing toward the center. Examples are both of left and right handed drawings. Make up your own version of the profile if you wish.

- Next, draw horizontal lines at the top and bottom of your profile, forming top and bottom of the vase.

- Now, redraw the profile on your “Vace/Faces” pattern. Just take your pencil and go over the lines, naming the parts as you go, like this: “Forehead… nose… upper lip… lower lip… chin… neck.” You might even do that a second time, redrawing one more time and really thinking to yourself what those terms mean.

- Then, go to the other side and start to draw the missing profile that will complete the symmetrical vase.

- When you get to somewhere around the forehead or nose, you may begin perhaps to experience some confusion or conflict. Observe this as it happens.

- The purpose of this exercise is for you to self-observe: “How do I solve the problem?”

Begin the exercise now. It should take you about five or six minutes.

Why you did this exercise:

Nearly everyone experiences some confusion or conflict while doing this exercise. A few people experience a great deal of conflict, even a moment of paralysis. If this happened to you, you may have come to a point where you needed to change direction in the drawing, but didn’t know which way to go. The conflict may have been so great that you could not make your hand move the pencil to the right or the left.

That is the purpose of this exercise: to create conflict so that each person can experience in their own minds the mental “crunch” that can occur when instructions are inappropriate to the task at hand. I believe that the conflict can be explained as follows:

I gave you instructions that strongly “plugged in” the verbal system in the brain. Remember that I insisted that you name each part of the profile and I said, “Now, really think what those terms mean.” Then I gave you a task (to complete the second profile and simultaneously the vase) that can only be done by shifting to the visual, spacial mode of the brain. This is the part of the brain that can perceive and nonverbally assess relationship of sizes, curves, angles, and shapes.

The difficulty of making that mental shift causes a feeling of conflict and confusion – and even a momentary mental paralysis. You may have found a way to solve the problem, thereby enabling yourself to complete the second profile and therefore the symmetrical vase.

How did you solve it?

- By deciding not to think of the names of the features?

- By shifting your focus from the face-shapes to the vase-shapes?

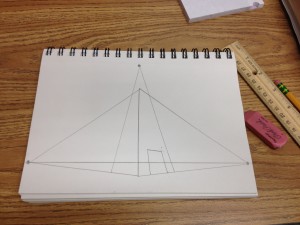

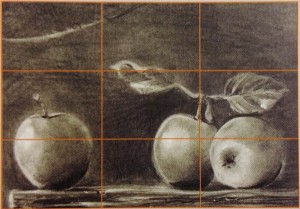

- By using a grid (drawing vertical and horizontal lines to help you see relationships)? Or perhaps by marking points where the outermost and innermost curves occurred?

- By drawing from the bottom up rather than from the top down?

- By deciding that you didn’t care whether the vase was symmetrical or not and drawing any old memorized profile just to finish with the exercise? (With this last decision, the verbal system “won” and the visual system “lost.”)

Did you use your eraser to “fix up” your drawing? If so, did you feel guilty? If so, why? (The verbal system has a set of memorized rules, one of which may be, “You can’t use an eraser unless the teacher says it’s okay.”) The visual system, which is largely without language, just keeps looking for ways to solve the problem according to another kind of logic – visual logic.

To sum up, the point of the seemingly simple “Vase/Faces” exercise is this:

In order to draw a perceived object or person – something that you see with your eyes – you must make a mental shift to a brain-mode that is specialized for this visual, perceptual task.

The difficulty of making this shift from verbal to visual mode often causes conflict. Didn’t you feel it? To reduce the discomfort of the conflict, you stopped (do you remember feeling stopped short?) and made a new start. That’s what you were doing when you gave yourself instructions – that is, gave your brain instructions – to “shift gears,” or “change strategy,” or “don’t do this; do that,” or whatever terms you may have used to cause a cognitive shift.

There are numerous solutions to the mental “crunch” of the “Vace/Faces” Exercise. Perhaps you found a unique or unusual solution. To capture your personal solution in words, you might want to write down what happened on the back of your drawing.